How to properly vent a roof for mold prevention

Venting an attic is simple, right?

Sounds easy – follow the code calculations, install a few RVOs or a ridge vent and make sure you’ve got decent soffit vents. Yet many attics with ventilation far superior to the code requirements suffer from mold issues. And many homes with terrible attic ventilation are completely mold-free.

Nope – venting an attic is actually pretty hard

Here’s how ventilation is supposed to work

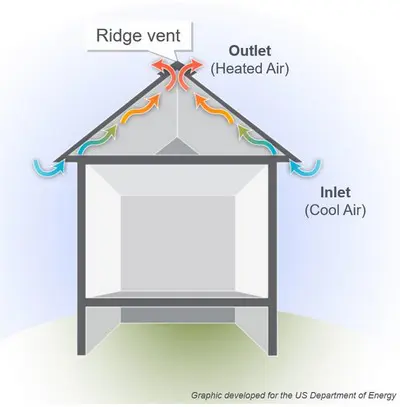

Attic ventilation is a two part process. First, air enters through the soffit vents. These are often round holes with wire mesh called ‘bird blocks’. Other common soffit vent styles include the perforated panels or slots on underside of the soffit. Technically the air is drawn in through the soffits via suction, rather than entering on its own accord.

Soffit vents provide intake air

Once the air enters the soffits, it moves along the underside of the roof sheathing. As it flows across the sheathing, moisture is pulled away along with the air movement. This prevents condensation (and mold growth in the attic) from occurring. Eventually, the airflow reaches the top and exits through the upper roof / ridge vents.

On breezy days, the process is aided by the wind. However, the wind is not reliable enough and therefore the process depends on the upward movement of warm air. As you recall from physics class, warm air rises. When a home is heated, a significant portion of that heat escapes upward into the attic. As the air in the attic warms, it begins to rise upward. When an attic is working correctly, this rising air finds an opening in the roof (either a ridge vent or RVO) and exhaust to the outside. As air moves out the upper roof vents a mild suction is created, which pulls air in through the soffits.

Problems

These air movements and pressure differentials are very slow. Imperceptibly slow. Even a minor impediment can stop the process completely. A bit of framing in the way is enough to stop the process. This is when mold growth occurs. The moisture in the air lingers a bit and the roof sheathing begins absorbing the moisture.

NOTE: Technically, we’d much prefer to see all attics converted to conditioned spaces and the ventilation completely removed. But that’s not likely to at a large scale any time soon. So for now, we’re stuck with attempting to improve a fundamentally flawed approach.

Common attic ventilation problems

Soffits blocked by insulation batts

Ventilating an attic properly can be very tricky. But some problems are simple. Like stuffing the soffit vents full of insulation… Unless a roof has a very steep pitch, the fiberglass batts must be tapered down as they reach the soffit venting. The venting problem can also be solved by pulling the batts back from the edge, but this leaves a dead spot which can lead to mold on the sheet rock corner in the room below.

Baffles installed in soffits, but crushed by insulation.

Insulation baffles work great. When they’re installed correctly… Baffles are typically made out of flimsy cardboard. This is more than sufficient to keep blown-in insulation away from the soffits. But they are not nearly strong enough to withstand the expansion force of a compressed fiberglass batt. In many of these situations, the batts looked great when they were first installed. However, in the days and weeks after the project was completed, the force of the insulation eventually crumpled the batts and blocked the soffits.

Hip Roofs

A hip roof is basically a pyramid with a flat top. The ‘hips’ are the long, angled ridges connecting the lower corners to the top horizontal ridge. These are very challenging because they greatly reduce the amount of space available for upper roof venting. Notice how there’s only one upper roof vent in the photo below. While the soffit venting may be excellent, the ratio of upper to lower venting is wildly disproportionate.

It gets worse. Hips are built with a tall rafter running along the length of the ridge/hip. This framing is usually quite stout (i.e. tall) and therefore it impedes the movement of air up the roof line. The air becomes trapped in these triangular sections of framing. You can have perfect soffit venting, but it won’t accomplish much because the air has nowhere to go.

Roof Valleys

A roof valley creates the same problem as a hip. A “valley” occurs where two roof lines intersect. Just like a hip roof, these valleys create dead spots of stagnant air. Venting these sections is nearly impossible; you’d need a separate vent in every single framing bay.

Mechanical ventilation options

Sometimes passive ventilation is insufficient or impractical. Low angle roofs, for example, struggle to produce sufficient air flow and often rely on mechanical assistance. Heavily gabled roofs, with a wide footprint and minimal ridge area, also suffer from poor passive ventilation and may require an active system. In a commercial setting, mechanical ventilation is often achieved through wind powered turbine vents. These work especially well in areas with consistent wind. However, they are unsightly for residential applications and most homeowners elect to install electrically powered roof vents instead. These are mounted on either the upper portion of the roof or on a gable end.

Remember, a powered roof vent still requires sufficient intake air if it has any hope of properly venting the attic space. In fact, if proper intake air is not provided, the fan will pull warm, humid air from the home rather than from the soffit vent. This would only compound the condensation and mold problems.

Perfect ventilation, but still mold growth? Yep.

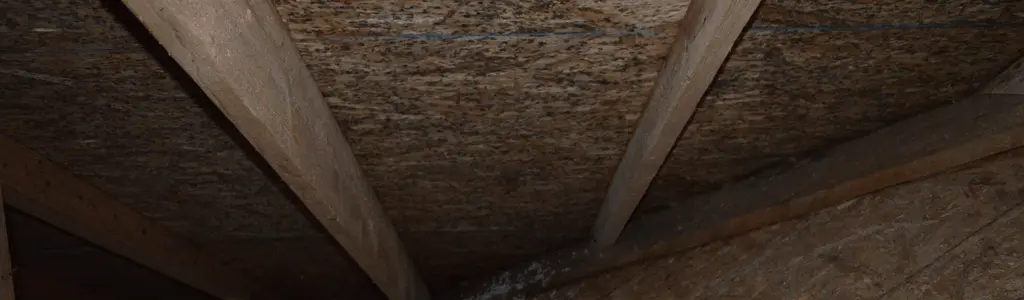

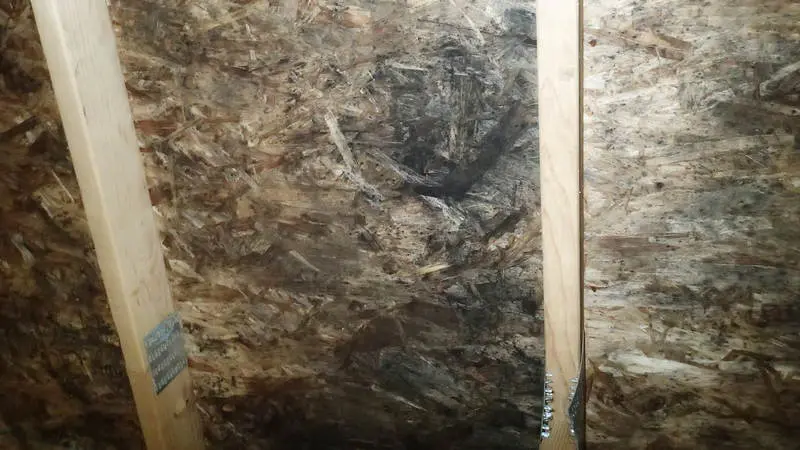

Often attics perform poorly because someone made a clear mistake. The venting was installed incorrectly, the quantity was insufficient, the insulation is blocking the vents, etc. These problems are very common. But there are also many attics that are genuinely hard to vent right. Look at the photo below. Despite perfect soffit ventilation, mold growth is covering the roof sheathing.

Example of bird block soffit venting

In the image below, mold growth is occurring right next to a well installed ridge vent. The photo at the very top even shows condensation occurring directly on the ridge vent. Why is mold growing on well ventilated attics?

Example of ridge vent

High indoor humidity

Typically this is caused by a poorly vented interior which leads to high humidity in the home. Over time, this moisture moves upward into the attic. Even the most well ventilated attics will struggle to overcome this additional burden of moisture.

Below is an example of a home with excellent ridge and soffit venting. Despite this ventilation, mold growth was still occurring on the sheathing. The solution? Increase the ventilation inside the home with a constant flow bathroom fan. Air sealing the ceiling will also dramatically reduce the amount of moisture entering the attic space.

Attic venting best practices

Passive or mechanical?

Attic ventilation can be broadly divided into two groups, passive and mechanical. As the name implies, passive venting does not include any motorized equipment or moving parts. These systems rely on the natural upward movement of air to exhaust humidity from the attic space. Think soffit vents, ridge vents, RVOs, etc. The natural air currents provide the necessary flow to vent the attic. In the vast majority of cases, passive venting is preferable. It’s reliable and silent.

What causes the air to move through the vents?

Passive attic vents rely on the ‘stack effect’. This is the principle of warm air rising within a home. The same is true in your attic. The air in attic is heated by a combination of solar radiation and heat loss from the occupied area below. This heated air begins flowing upward. In a correctly vented attic, this air will exit through the upper roof vents. As the air exits, the attic will depressurize and seek to bring in air to equalize the imbalance. In a correctly vented attic, the soffit vents will provide this airflow.

Passive ventilation will not work in all homes. For example, many houses from the early 20th century does not have any soffits whatsoever. Flat or low angle roofs also perform poorly with passive ventilation. You can have all the venting in the world, but without a decent slope, the air has no motivation to exit the attic space. Pyramid/hip roofs can also be difficult to vent passively.

Notice the lack of roof overhang. Adding traditional soffits is impractical.

How much venting do I need? Code requirements for attic ventilation

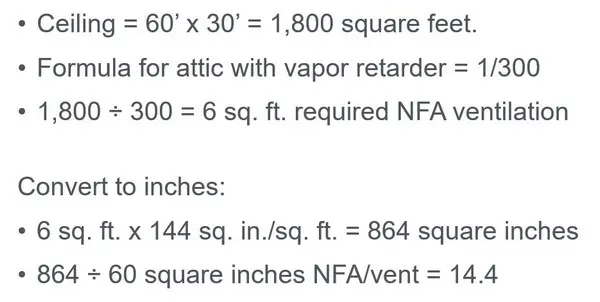

Most regions require a ventilation ratio of either 1/150 or 1/300. I.e. for every 300 square feet of attic space (measured at the ceiling) you need 1 square foot of ventilation. Note, this is NFA (net free air flow), which is the true air flow through a given vent. This is significantly less than the simple measurement of the vent. The vent manufacturer will supply the NFA with the product.

The 1/300 figure is for homes with a vapor retarder installed on the ceiling. In most cases, this is supplied via a low perm latex ceiling primer. In reality, this distinction is a bit silly, as the penetrations in the ceiling will allow far more moisture transport than the material itself. 5 layers of low perm primer is meaningless if you have leaky can lights distributed throughout the ceiling.

*The code varies by region, so be sure to check with your local building officials.

Example Calculation

Make sure it’s balanced

Passive vent systems required an equal distribution of ventilation between the soffit and upper roof area. An uneven distribution of vents can cause make-up air to draw inward from upper vents instead of the soffit vents. A typical attic would require a 1/600 ratio at the soffit and another 1/600 at the ridge. Using the example above, this roof would require a total of 864 square inches of ventilation (432 square inches at the ridge and 432 at the soffit).

Some brands, such as Air Vent make this easy by labelling their products with the NFA directly in the name. For example, their RVG40 Slant Back vent provides 40 square inches of net free area. The roof described above would require 11 of these units. Externally baffled ridge vents provide an amazing amount of NFA. For example, the Owens Corning model is rated at 20 square inches of NFA per linear foot of ridge vent. A 30′ length of ridge vent would provide 600 square inches of ventilation, far more than available from reasonably spaced RVOs.

A hip roof is a great example of the importance of balanced ventilation. If your upper roof venting is limited to a handful of RVOs, it offers little benefit to keep adding soffit vents.

Types of passive vents

Ridge Venting

These are long, continuous strips of ventilation that sit directly on the ridge of the roof. They are available in two types, externally or internally baffled. The externally baffled models can be highly effective. Internally baffled models are often worthless.

Internally Baffled Ridge Vents

These ridge vents basically look like multiple layers of a corrugated cardboard box (though they’re made out of plastic). They have one thing going for them – they’re cheap. On the negative side – they don’t seem to pass much air through them. As you can see in the photo below, the channels are very small. The air flow in an attic is very slow, so any impediment will drastically reduce the movement of air.

Externally Baffled Ridge Venting

As the name implies, externally baffled ventilation relies on barriers on the outside to prevent water intrusion. This allows for much larger openings in the actual ventilation portion of the ridge vent. These ridge vents also sit significantly taller than a typical internally baffled model. This also allows for great air flow.

Many externally baffled models are built with a plastic fin on the outside edge. This is designed to create a low pressure zone over the vent as wind moves over the ridge. In the Pacific NW our wind is fairly irregular, so this feature should not be relied upon.

Yes, they can become clogged with needles, but I’d still be on a clogged externally baffled ridge vent over an internally baffled model.

They often arrive with a loose mesh to prevent bugs from entering the attic. They can become clogged with dust and debris and cut down on the air flow. We typically recommend removing the fabric unless there is a history of pest issues.

Case Study – Code Compliant, Yet Mold Growth

Clients often ask us about the code for attic ventilation. In most cases, the code is sufficient. But there are numerous exceptions. The following project met the 1/300 sqft rule for attic ventilation. As you can see in the photo, the soffit vents are interrupted at the front of the home by the bump-out dormers. Even with this limitation, the total soffit venting handily beat the code minimum. Yet despite meeting code, the roof sheathing suffered from mold growth.

Lack of air sealing

Most homes, unless recently built, lack air sealing. This allows warm, moist air to easily enter the attic. As the moist air impacts the cool roof sheathing, the moisture condenses on the surface. Over time, this leads to mold growth.

Solution:

- Air seal ceiling penetrations

- Add upper roof vents

- Increase indoor ventilation via a constant flow exhaust fan

*Heads up – I earn a small commission on sales through Amazon links. This helps cover the expense of running the website (and answering your questions!)

Got a question? Ask it here and we'll post the answer below

Can air sealing an attic space cause mold growth?

No, air sealing an attic will reduce the likelihood of moisture entering the attic. This dramatically lowers the odds of mold growth. The only potential downside of air sealing is the increased humidity inside the home. This can be easily addressed by increasing your ventilation via your bathroom fans.

Is it ever wrong to have ridge vents? Do ridge vents ever cause mold?

This depends on the type of ridge vent. Externally baffled ridge vents are excellent and provide uniform ventilation throughout the entire upper roof area. Low profile, internally baffled ridge vents are not nearly as effective. Unfortunately, the internally baffled models are far more common.

Is it ever wrong to have ridge vents? Do ridge vents ever cause mold? on the roof?

Ridge vents are great, if you pick the right model. In the article above, you’ll see photos and a description of externally baffled ridge vents (vs internally baffled). These perform very well in the field. If you’re still encountering mold issues with these installed, it’s due to some other issue (poor air sealing, excessive insulation, blocked soffit vents, etc.)

My roof contractor recently installed a rubber roof to avoid water entry from ice damming. In the process they removed all ridge vents and closed them up with the rubber membrane. They now tell me there is no more need for ventilation. The soffits are still open, and nothing else has changed. I call BS. Who is right?

You are correct. Switching from a composition to a membrane roof does not alleviate the need for ventilation. You’ll still need ridge/upper roof ventilation to avoid mold and rot. The soffit vents are useless without a corresponding exit point near the top of the roof. Air is drawn in from the soffits due to the negative pressure created by warm air rising out the ridge area vents. Therefore, if no ridge area vents are present, the air in the attic won’t move, regardless of how many soffit vents you are present. If the roofer doesn’t want to use a ridge vent, they could add RVOs on the composition side of the roof, just below the top. I’d recommend installing these in every other bay (every 4′).